Using Git

When it comes to Software Version/Configuration Management, there might be a whole lot of vendor or open source implementations to choose from but in recent years, there’s none that could parallel Git in terms of being the most development/hacking friendly.

I’ve used quite a few different forms of software management tools, from the CVS/SVN family to the Clearcase/Perforce family (which I personally feel is absolutely horrible) but it is with Git that I finally think that Software Versioning is no longer a necessary evil but something that actually helps in the software development process. Perhaps, I will need to corroborate my statement with some examples later but using Git can actually encourage developers to experiment and be creative in their code, knowing that they can always reset back any code changes without any penalty or overheads.

I would not want to spend too much time talking about Git’s history. (if you are interested, you can always read wikipedia. If you are like myself, who was previously using CVS/SVN or Clearcase/Perforce to manage your software, I hope this article would improve your understanding on how Git works and how it could increase your productivity as well.

How a distributed version control system works

As the name suggests, a DVCS does not require a centralised server to be present for you to use it. It’s perfectly fine to use Git as a way to store a history of your changes in your local system and it’s able to do so efficiently and conveniently. However, as with all Software management tools, one of the main benefits is to be able to collaborate effectively in a team and manage changes made to a software repository. So how does Git (or any DVCS) allow you to work in a standalone manner and yet allow you to collaborate on the same codebase?

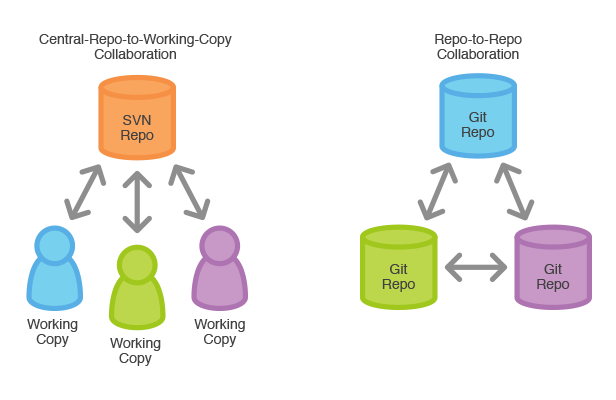

The answer is that Git stores a copy of the whole software repository in each local machine that contains the codebase. This might seemed like a very inefficient and space-consuming method but as a matter of fact, this wouldn’t be a big issue if your files are mostly text (as most source code are) and these files are usually stored as a blob (and highly compressed). So when you use Git, you are actually working within your local environment and this means that besides a few commands that do require network communications, most commands are actually pretty responsive. When you “commit” code into a Git repository, you are not actually in a “collaborative” mode yet as your codebase is actually stored in your local system. This is a concept that is somewhat different from other VCS systems where a “commit” actually puts your latest changes into a common repository where everyone can sync or access it. The concept can be simply illustrated with the following image I pilfered from Atlassian’s site here :

So that being said, how do I actually share my code with the rest of my team ? The wonderful thing about Git is that it allows you to define your workflow. Do you want to synchronize your code directly with your peers? Or would you prefer a traditional “centralized” model where everyone will update the “centralized” server with their code. The most common way is the latter where each developer or local workstation will synchronized their codebases with this centralized repository. This centralized repo is also the authoritative copy of the repository which all workstations should clone from and update to.

So, for the centralized model, everyone will perform a “git push” to this central repo which every workstation will nominate as its “origin” for this software repo. Before a “git push” succeeds, git will need to ensure that no one else has actually modified the base copy that you have retrieved from this centralised server. Otherwise, Git will require that you perform a “git pull” to merge the changes performed by others into your local server (which might sometimes result in a conflicted state if someone changes the same files you have). Only after this is done will you be allowed to push the new merged commit to the server.

If you have yet to make changes to your local copy and there’s a new commit in the “centralized” server since you last synchronization, all you need to do is perform a “git pull” and git does something called a “fast-forward” which essentially is to bring your local copy to the latest code from the centralized server. If all this sounds rather convoluted, it is actually simpler than it sounds. I would recommend Scott Chacon’s Pro-Git book which explains clearly Git’s workings (here’s a link to his blog)

So what if it’s DVCS?

When you use Git in your software development, you will start to realise that making experimental code changes is not as painful as it used to be with other tools. And the main reason for that would be the ability to do a “git stash” whenever you want to .. or a “git branch”, which as the name implies, creates a new branch off your current working code. Branching in Git is an extremely cheap operation and it allows you to define an experimental branch almost instantaneously without having to explain yourself to all your team mates who are working on the same code base. This is because you choose what you want to push the “centralized” Git repo. Also, whenever you need to checkout a version of the software from history or remote, you can “git stash” your work into a temporary store in the Git repository and retrieve this stash later when you are done with whatever you need to do with that version.

Ever tried creating a branch in Clearcase or Perforce? I shudder even at the thought of doing it. SVN does it better but it is still a rather slow operation which requires plenty of network transfers. Once you have done branching using Git, you will never want to go back to your old VCS tool.

blog comments powered by Disqus